Internet Infrastructure Predictions for 2023 (Part 1)

Looking back, I suspect 2022 will be remembered as a year in which conflicts and crises shaped our collective attitudes toward infrastructure and the Internet in interesting ways.

- In Russia’s war against Ukraine, we had to contemplate the implications of a war with a significant Internet component, waged increasingly against civilian infrastructure.

- Canadians struggled with massive multiday outages of fixed-line and mobile Internet services that affected the economy from top to bottom, raising questions about the threats of significant market concentration.

- Changes at Twitter drove millions of people to reconsider the convenience of centralized social media platforms and think about the responsibility that comes with hosting their own small piece of decentralized infrastructure.

All of these things forced us to reconsider what had felt like long-settled orthodoxies and Internet norms. 2023 will be a year in which we consider whether we might, collectively, need to reconsider our relationship with centralized infrastructures and how we defend and promote the open Internet against the threats it faces.

As luck would have it, I spent much of the last year as a volunteer resident advisor with the Internet Society, learning from the Pulse, policy, and advocacy teams. Speaking only for myself, I’ve gathered a few observations and predictions for Internet outcomes in 2023 that I will share in a series of posts over the coming week.

Prediction #1: the Ukrainian Internet Will Survive the Intensifying Infrastructure War

Geopolitical concerns over Internet connectivity were nowhere more apparent in 2022 than in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Early Russian attempts to disrupt Internet connectivity in Ukraine (Viasat in February, Ukrtelecom in March) had little impact. Cyber attacks then gave way to kinetic strikes, as missiles targeted communications infrastructure, and engineers from Kyivstar, Lifecell, Triolan, and other providers worked continuously to patch and restore service. By June, Russia had rerouted the Internet of occupied Kherson through their own territory.

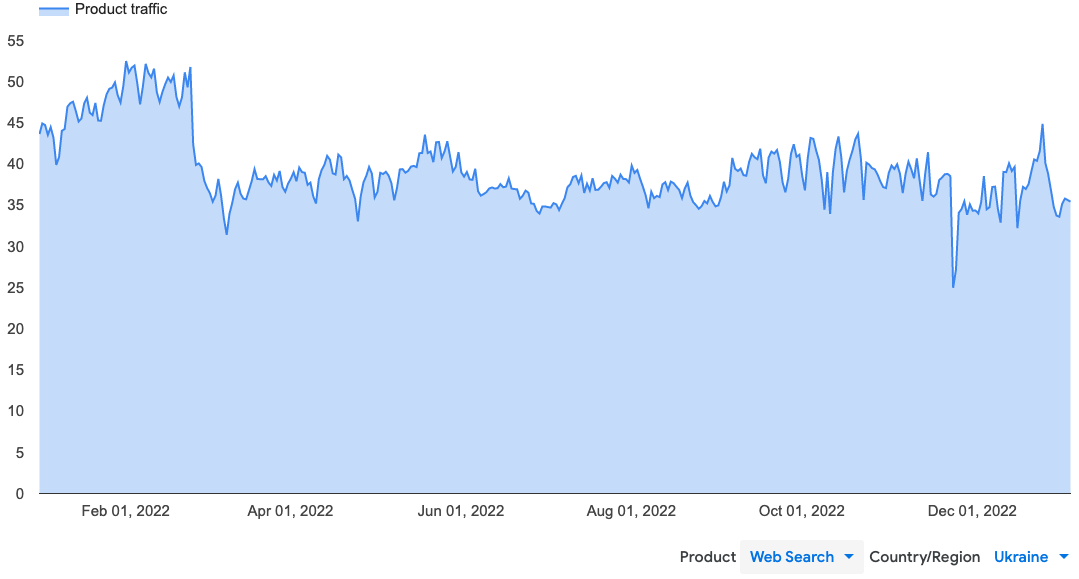

Still, the impact on the Ukrainian Internet remained limited, as suggested by Google’s report of inbound search traffic from Ukrainian networks (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Time graph showing inbound search traffic from Ukrainian networks 1 Jan 2022 - 5 Jan 2023.

Figure 1. Time graph showing inbound search traffic from Ukrainian networks 1 Jan 2022 - 5 Jan 2023.Source: Google Transparency Report

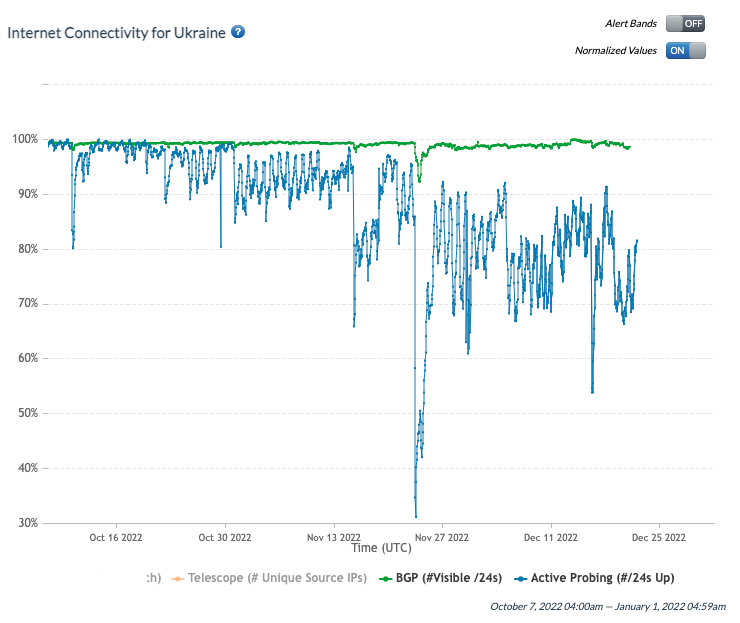

Only as Russia has begun to deliberately target civilian energy infrastructure, has the aggregate reachability of Ukrainian networks begun to sag, as made visible in the Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) report for the 90 days ending 5 January 2023 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Time graph showing the Internet connectivity in Ukraine from October 2022 to December 2022. Note the reduced connectivity for Ukrainian networks in the global routing table (green) and the smaller local networks (blue), which can be attributed to Russian missile strikes on power infrastructure.

Figure 2. Time graph showing the Internet connectivity in Ukraine from October 2022 to December 2022. Note the reduced connectivity for Ukrainian networks in the global routing table (green) and the smaller local networks (blue), which can be attributed to Russian missile strikes on power infrastructure.Source: IODA (ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu)

The fact that the unreachability of smaller networks is not prominently visible as a corresponding reduction in Google’s aggregate search traffic suggests that the affected networks support fewer active users while the majority of the population retains connectivity. Except for broad, nationwide outages like the one on 23 November, the Ukrainian Internet continues to function for its end users, subject to the intermittent availability of power. In 2023, expect to see more of the same resilience.

Prediction #2: The Internet in Central Asia Will Find Better Alternatives

Part of what makes the Internet special is that having a few good neighbors can make it a lot better. Ukraine’s Internet has survived Russian attacks in part because it builds on a legacy of decades of domestic provider diversity, a healthy set of IXPs, multiple cross-border fiber paths, and relationships with providers in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Warsaw, Budapest, Vienna, and Sofia.

Regional conflict can also help find creative solutions to long-standing problems. When we look at the countries east of the Caspian Sea (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan), it’s interesting to speculate: will 2023 be the year when they finally achieve new levels of international provider diversity?

I shared some thoughts in November at the inaugural Central Asian Peering and Interconnection Forum (CAPIF-1) about how the geopolitics of trade and interconnection might play out — watch the recording.

For years, Central Asia’s connectivity requirements have been met (expensively, with high latencies) by connecting to Russian providers, who carried their traffic to European exchange points. This year, more than ever, change is in the air.

Figure 3 - Map of Central Asia with overlay of anycast service footprint of Google’s public DNS.

Figure 3 - Map of Central Asia with overlay of anycast service footprint of Google’s public DNS.Source: CAPIF1

In my presentation, I mapped the anycast service footprint of Google’s public DNS (8.8.8.8) to give a sense of the kinds of ‘Internet watersheds’ that might lie within reach of Central Asian ISPs in 2023:

- Green represents the status quo: connectivity northbound through Russian providers to Google’s servers in Finland.

- Brown represents submarine cable paths to Milan.

- Blue represents terrestrial paths through Turkey and Bulgaria to Zurich.

- Purple and red represent farther-afield possibilities in India and Hong Kong, respectively.

The best opportunities for improved Central Asian connectivity in 2023 will be the great unknowns: either a long-awaited fiber connection across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan or (more likely) the broader availability of Iranian terrestrial paths around the Caspian’s southern shore to connect with the Caucasus Cable System or with submarine landings in the Gulf. Either of these would open the floodgates to European, Middle Eastern, and Indian connectivity.

At the last meeting of CIS heads of state in Moscow on 26 December 2022, Kazakhstan’s President Tokayev made a special note of the emerging importance of the North-South Transport Corridor, of which the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran Railway is the centerpiece. Whether or not this corridor ever becomes a viable alternative path to market for Russian goods, the fiber route itself represents one of Central Asia’s best prospects in 2023 for finding complementary paths for Internet traffic that will quietly diversify this region’s historical dependence on Russian providers once and for all.

This post originally appeared on the ISOC Pulse Blog.